In other words, the great challenge.

I have hardly any education or experience about tailoring or pattern drafting for men in general. On the other hand, historical fashion needs a different kind of approach to cut and fitting anyway. When I began this project, I was still developing my eye for the period look, as I still am, of course. Nor did I have a very clear idea about the construction. As for the patterns, there are of course patterns taken from museum pieces, but unfortunately all I came across were not even close to Jarno's size, which makes getting the proportions right a bit more challenging.

Once again I was greatly aided by La Couturiere Parisienne's tutorial and also received some advice for friends. The rest I reasoned by myself, probably not always with the best results, but then I can always claim that this is my first one, right? When the suit was finally finished I was actually a bit bewildered that I had ever managed to finish it at all.

Dating the suit loosely about mid 18th century

was first and foremost based on aesthetics, as I'm rather fond

of the look. At this point the silhouette had already narrowed

a bit from the flamboyant wide skirts and gigantic cuffs of

the 40's, but had not yet developed into the slender style of

the later century. My own taste runs mainly from the

mid-century to 90's, so Jarno's outfit would more or less go

with everything I wear - you can always be conservative and

wear an earlier style even if your wife goes for for the

latest fashion fads.

Choosing the material was very easy. Black is

always a safe choice, and wool is both period correct and nice

to work with. I have to confess, though, that the material I

chose (as it was somewhat affordable) has some polyamide too.

The sole decoration are brass buttons. The waiscoat was

originally planned to be of the same black material as the

coat and breeches, and I was slightly surprised when Jarno

declared that he wanted something fancier after all. We didn't

have much time to search, so luckily we soon found a nice

furnising material which really adds to the look. Even though

the waistcoat is an important part of the suit, I've chosen to

create a page of it's own for it - mainly to prevent this

project page becoming impossibly long.

The patterns are a mixture and interpretation of the following sources: La Couturiere Parisienne, Norah Waughs "The cut of Men's Clothes 1600-1900” and the pattern for a mid-century military uniform provided by The Olde Militia of Helsinki. Duran Textiles also had a detailed article about a swedish mid-century suit in their newsletter, which I found very informative.

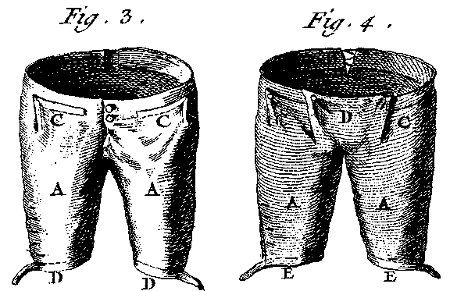

Let us begin with the breeches, with which I began the project even before I had any idea of the patterns for the rest. It's best to handle such a big project on smaller units if possible.

I chose the earlier style for the waist with a fairly modern fly, instead of the later fall-front style. According to Duran Textiles the latter only came in use in Sweden on the 70's, though it was obviously in use in France already in the 50's - exact dating aside, the main reason was that it seemed easier to me. Having made this main style choise I gathered Jarno's measurements and all my pattern sources together and began to draft a pattern.

One of my teachers used to compare drafting trouser patterns to dark arts, and I think she may have been quite right. 18th century breeches also differ somewhat from modern trousers. They fit snugly at thigh while being baggy at the hips, especially at the beck, so one can sit comfortably, and the long coat conveniently covers the bagginess anyway. Convenient for the final outcome, not so convenient for research in paintings. Like I already mentioned, the patterns I had were way too small for Jarno. My own experiences with making pants for myself have always been mostly about how to get them large enough at the hips and bottom and yet small at the waist, so that didn't particularly help. Even at this age you can still learn the difference between male and female anatomy...

One of my biggest questions was how high the waist was supposed to rise. According to the patterns the waist seemed still to sit quite low at this period, but a little bit higher rise seemed somehow safer to me. Drafting the pattern was very much about trial and error, and if my memory serves me right the third or fourth pair of mock up breeches fit to my satisfaction. Luckily I had bought a lot of muslin from sale!

According to some sources, like La Couturiere Parisienne, the breeches were usually left unlined, but as I have seen museum pieces which seem to be lined I decided to make a lining - it so conveniently finishes everything and hides machine stitching and uneven seam allowances (like anyone would care anyway). I used a thin cotton batiste which I use for most things that need a breathing lining. Being totally pedantic I got the great idea to dye it black. My limited dying experiences include mostly pastel tones, but black was quite another thing. After two dyes it was still a very uneven dark blue. In the lining it would do, but then I realized that with sweat or rain the dye just might come off and stain the hand-sewn shirt. I wasn't very eager to take the risk so I bought some more batiste which stayed white.

After all the hassle with the patterns the sewing was comparatively easy. The directions for the construction come mainly from La Couturiere Parisienne. For the interlining in the waistband, and everywhere there would be buttonholes I used linen. Before making the breeches up I stretched the front pieces a bit at the thigh and tried to shrink the back pieces accordingly with steam iron.

I made everything I could with machine but all the finishing by hand. On the whim of crazy perfectionism I used the dyed batiste for the pocket bags and the fly, fearing that the white would peek out offensively - which might even have been totally period. I also used fabric covered buttons for the fly though rest of the buttons were brass ones, so that they wouldn't show.

The waistband

opens at the back and is closed with a lacing - this gives

some room for adjusting the size. The lacing holes are

handmade very tightly, which makes them really strong.

The kneeband should be fastened with a buckle, but as I was in a hurry I din't bother to search for a suitable one but made a buttonhole instead. Also I realized only after finishing the kneeband how it really should be attached (I hadn't understood the directions properly before), but I'm not going to do it again.

All the edges are finished with hand-stitching, which makes them neat and firm. The biggest job were the 20 buttonholes. I used silk buttonhole thread, which was really nice to work with and didn't get annoyingly tangled all the time.

The finished breeches fit quite nicely at first, but the first time Jarno wore them we noticed a big problem. New pants usually stretch a bit at the waist, and obviously the linen I had used for the interlining was not nearly strong enough to keep them in shape. Jarno had also lost some weight. So, after the first half an hour the pants were literally falling of all the time, especially as they are loose at the hips. Poor Jarno managed somehow through the day, and for the next day of the weekend-event I moved the moved the buttons as far as I could, which helped a little. Later he has used a non-period solution of suspenders. Well, at least he is unlikely to outgrow the breeches any time soon...

Not counting this little mishap the breeches weren't too hard to make. The next part of the suit

to attack was the waistcoat, which I made pretty fast - more about it can be found here. When it was the time to move on to the coat, I became more nervous.

As I already mentioned, I dated the suit loosely to mid-century. I had several pattern sources, but none was of course nearly the right size so I had to draft my own patterns and try to get them look like the period ones. I based the coat on the waistcoat pattern, which in turn was originally based on the modern waistcoat pattern I drafted for Jarno back in school. The coat pattern is really a combination of the different cuts seen on different sources and my own opinions and guesses about what might work best.

The front

edges are slightly curved, the collar that appeared later is

still absent. The lack of collar felt very odd at first but

after some time my eye got used to it. The skirts are still

quite full, the side slit has one 18cm deep pleat on the front

piece and two at the back piece. The total hem width is close

to five meters. While the hem is still cut wide, it's not

stiffened anymore. The cuffs are also still quite tall, but

not as wide as in the 40's.

I had most difficulties in determining where the back and side slits should end and similarly the vertical placing of pockets. Pattern width is always relatively easy to check with fitting, but vertical details are much harder to scale when you are working with a pattern in very different size. At last I simply chose what looked okay - which usually works well, but with historical stuff can go horribly wrong unless you already have well-developed period-eye. Even before the issue of the slits I had spent ages trying to decide where exactly to place the side seams - because of the pleats the decision would be final.

Another thing that puzzled me greatly was whether the coat should be wide enough to be buttoned or not, though a fancy suit was usually worn with the coat open. La Couturiere Parisienne says it should be large enough to be buttoned, but then again it seems to me that many fashionable coats in the period paintings look rather unlikely to button without strain. At last I ended up with a compromise, not adding the allowance for the buttoning but making it wide enough that it can for the most part be just buttoned if needed. Again, it looks decent to me.

The most

difficult part was, not very surprisingly, the sleeves. As I

have never made patterns for anyone even close to Jarno's size

the scale alone made me completely lose my touch. 18th century

sleeves also seem to have mysteriously low sleeveheads, partly

because they didn't use any padding on the shoulder (rather on

the breast, which I decided Jarno didn't need). Moreover, I

never managed to quite form an idea of the correct shoulder

fit, even though I stared at the portraits and costume films.

I theory I also knew that the sleeve should fit snugly at the

arm, but on the other hand I was afraid it would feel too

tight for Jarno who is used to looser fit - not to mention

that he has to be able to dance etc.

After some

mock up-versions, however, I decided to muster up my courage

and put scissors to the real material. I cut most of it with

regular allowances but left a wider allowance at the hem,

since the wide hem would stretch differently in different

parts anyway.

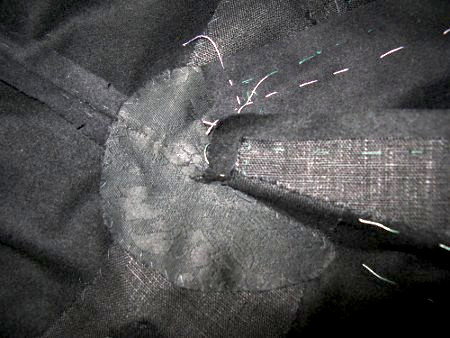

In this project I spend more time than usually with the preparation work, marking the pieces with basting and attaching the interlining by hand. For the interlining I used stiff linen, black which is a modern but also neat choice, as it just might peek annoyingly out of buttonholes.

I put interlining on the front edges, neck and the shoulder of the front piece. I also reinforced it still by adding a narrow strip on the front edge and other places where the linen would be cut in the bias, thus liable to stretching. It's fastened to the interlining pieces with zig-zag.

I also used interlining in the edges of the side and back pleat, and all around the waist, the last one adding support also for the pockets and the top of the side slits. I also interlined all the places where there would be buttons, since though they were quite lightweight they might get caught somewhere. Of course, pocket flaps and cuffs got their interlining too - on the afterthought, I could have added another layer at least on the cuffs. Attaching the interlining was quite relaxing as the black fabric with a nap hid the stitches without much effort.

Apart from the usual matching points I marked the button/buttonhole places, pocket place and the side pleat folds and the end of the slits with basting.

For extra support for the seams I basted cotton tape on the vertical seams and the shoulder seam to prevent their stretching. This was especially needed on the center back seam, which was cut almost halfway between straight grain and true bias. I also reasoned that the tape might protect the woollen material from the possible chafing of the stitches, especially at the said center back seam which always has to endure some horizontal strain, so I basted it on both pieces. I also added tapes on the lower, curved part of the sleeve and elbows to prevent them from getting baggy.

I had already some time before cut the pocket flaps and begun them, as I would need them almost at once when I'd begin sewing the coat, and it would be frustrating to begin then with the buttonholes, 8cm long and four of them in each flap. I had originally planned to use silk thread for them, but as it would have taken forever I bought more of the shiny viscose thread I had used for the waistcoat too. It got tangled very easily, but as it was thicker it speeded up the work which was very welcome.

Making up the suit began with mounting the pockets. Unlike in the waistcoat, this time I decided to cut the pocket bag wider than the pocket opening, simply stitch it on the marked edges with the right sides together, cut away the center of the triangle and turn the pocket back inside. I also rounded the corners of the triangular pocket opening to make this easier. I finished the pocket opening with hand-stitching, fixing the seam allowances in the process. Then I added the inner piece of the pocket bag, both of them reaching up to where the flap would be attached to fix them in place. I attached it with machine (it felt like I only got to use machine a few times in the whole project amidst all the hand-sewing) but turned the top edge allowances under, where the lining of the flap covered them, making this by hand which was quite tricky to get neatly done.

The next thing was the first real seam, the back seam. Only after closing the seam I attached the horizontal interlining band over it. Then I added the back inserts, which was rather exciting in the very tight corner in the flared back piece (the fold caused by this can be seen on the picture). I backed the corned with a piece of linen. After adding the back inserts forming the back slit, I fixed the top of their interlining, which extended over the seam and was fixed on the horizontal band in the waist. I reasoned all this would protect the seams against the weight of the skirts, and also the strain if they were caught for example when sitting. Despite being relatively thin and slightly shiny the woollen fabric disguised all the supporting layers which were rather thick at some places.

Having now both front- and back pieces ready it was the time to put the side seams together. As I was completely obsessed by the thought of the strain the heavy pleats would put on the seam, I wanted an even stronger interlining for the top of the side slits (as is also advised in period manuals). Having closed the seam I added a rounded piece of very thick canvas.

Then I closed the shoulder seams and made up the sleeves. I added some light wadding on the sleeve head, like I might do in a modern coat to help to disguise the thick seam allowance. Then I folded and pinned the side pleats, and it was the time for the first fitting.

On the fitting the coat looked pretty good, apart from the sleeve which still didn't quite work. At this point I decided it would do, however.

It was the time to make the lining. I used the same thin black linen as is the waiscoat. Even though I'm aware that period linings were usually light, I couldn't get past my obsession of black lining for a black coat. Thin white linen would also have been too transparent with black, and silk was out of the question for budget reasons.

Cutting the lining was a pain, since I had prewashed the linen to prevent further shinkage, and while drying it had obviously stretched somewhat at some places. Thus the edges weren't running straight anymore. Having finally managed to cut it and made it up I sew it on the front edges from the waistline upwards. I also attached it at the top of the side pleats, and not knowing the correct method I just made it as it felt convenient. Then I put the coat on my dummy and let it hang there for some days so that the wool and the lining would both stretch as much as they eventually would before I put them together.

Making two different bias-cut materials to co-operate turned out not so easy. I pinned, basted and ironed again and again but every time there was bagging somewhere or the edge turned inside. I think the lining was really off the grain at some places when I cut it, since the other slit was slightly better than the other. I also think that the top fabric's slit edges may have stretched a bit before I put on the interlining, what I should have done would have been to check the length from the pattern when cutting the interlining band. The front edges also caused similar problems though on a smaller scale.

I spent some

time raging and cursing and deciding I would never again touch

anything bias cut ever, but at last I managed to get the

lining work somewhat decently. Unfortunately I didn't have

very wide seam allowances but I worked with what I had. The

result is that in some parts the lining begins more than 0,5cm

from the edge, but as it's black it doesn't really show.

So, at last I could baste the hem and cut it even. After the fitting I was extremely reluctant to undo my basting, turn the coat over and try to get the lining match, no matter how many matching points I might have cut. Instead I chose the period method of folding the edges under and finishing the hem by hand, which I really should have done with the front edges too. From the waistcoat I had already learned that a modern vertical allowance in the lining definitely does not work. Anyway, the sewing went amazingly fast, and I'm rather confident that machine made bag lining would have needed so much adjusting and possibly redoing that it might not have been significantly speedier. I also figured out almost by accident how to do "Le point a rabattre sous la main", which had sounded difficult in theory but at least on a soft and not very thick material was dead easy. It means to sew the folded edge of the lining about 1-2mm from the edge so that your stitches go partly through the edge to the right side, so that the result is like a neat bag lined edge with supportive hand stitching all at once. Brilliant.

I had put off the troublesome sleeve as long as I possibly could, but now was the time to confront it. With the cuff I had chosen a shamefully modern method of sewing the cuff and the turning allowance together with the lining and leaving the lining to fold a bit. Then I had put the sleeves on, machining them and all, but they just kept hurting my eye. To be more precise, my interpretation of the 18th century sleeve as seen on the original patterns, with low sleevehead and markedly shaped elbow just didn't seem to work for Jarno. With hindsight I think the sleeve might have worked slightly better had it been tighter at the arm, but like I mentioned, I wanted Jarno to be comfortable in it. Anyway, at last I decided I couldn't live with them, and took them off and began anew from the scratch.

From my pattern sources the one of The Olde Militia of Helsinki seemed the most simple and likely to fit - perhaps because as it is meant for more practical military wear. At this point I had decided to forget all things period and make the sleeves however modern if I could only get them to look decent by any standards, though. So, I took a new aproach, trying to draft a more modernly shaped sleeve that would fit Jarno. I drew the sleevehead considerably taller and finally took out much of the curve on the elbow. Luckily I still had plenty of material (as I usually buy too much) to redo the sleeves completely. Luckily also the cuffs fit the new sleeves.

After the battle of the sleeves I still had buttonholes and some more finishing touches to do. Having begun the coat on my summer vacation (on August), I had spent so much time with it (or avoiding it) that the Christmas ball was approaching fast at this point. Which was a good thing, otherways it would have probably taken a much more time to finish this project. The last days before the ball I spent with the buttonholes, also pressing the side pleats a bit more and finishing our masks. The side pleats were still troublesome, and I had to press them yet again and change them slightly. I also fastened some of them with a few stitches. With hindsight it might have been better not to mark the pleats on the pattern but rather experiment where they would naturally fall, but then again I might also have gone insane trying to get them even then.

The side slits also got smaller buttons and buttonholes (which I made with silk thread this time, as they were smaller). The real purpose of the side slits is, by the way, that gentlemen could carry a sword without it getting tangled awkwardly in the skirts of the coat. At last I had to give up and leave the last six buttonholes on the back slit to be added later, as they are kind of optional. It took another several months to get them finally done again!

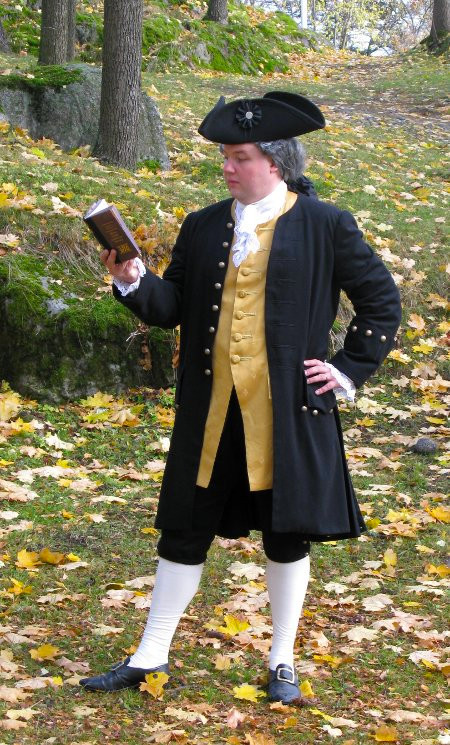

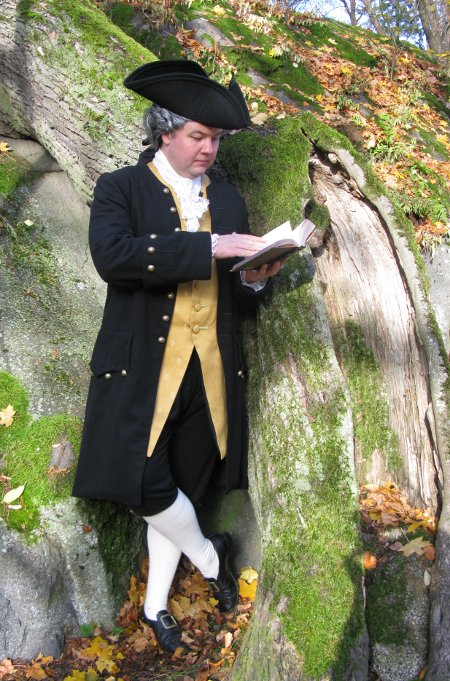

So, Jarno got his suit for the Christmas ball, but it took almost a year before we finally got around taking decent pictures of it - we have already learned that events are not the best oppurtunity for shooting, since you are often in a hurry and lack the mood to really concentrate on taking a lot of pictures. On the other hand, this procrastination gives a chance to judge how the suit has worked in use.

I'm still not

100% satisfied with the sleeves, they work so and so but are a

bit too modern. I think part of the problems I had with the

sleeves comes simply from the shape of Jarno's shoulders, as

he has a very straight shoulder line, not stooping at all like

was the period fashion. Some of his modern clothes fit a bit

awkwardly too and I have for a long time tried to figure out

why. When I made my own riding habit later, the low period

shoulder line and sleeve, which came almost straight from a

reference pattern, fit me quite well with only minor

adjustments.

The side

slits have also been troublesome, but now I think I have

finally gotten them to settle down after pressing them yet

again, changing the line of the outer one once again. I should

originally have followed more where the folds would naturally

settle than to just stare blindly at my neat pattern.

After finishing this suit I felt I would never, ever attempt the same again, but now, after some time has passed I occasionally find myself thinking that Jarno might get another one some day. Not very soon though! I will have a lot to experiment and improve yet, which is of course also part of the fun of dressmaking.